The Hon. Charles Stewart Rolls

Since there is a great and sad story behind this pioneer of British aviation, I wanted to put the case for remembering him, and also attempt to relate the significance of the British International Aviation Meeting at which he met his death in 1910.

Known at university as Dirty Rolls because of oily hands from his endless work on engines and more generally to his friends as Charlie Rolls, he became well-known as a national hero in his own short life, graduating from cycling to motorbiking to car racing to ballooning, and finally flying. He met with Henry Royce to form and finance Rolls-Royce Ltd. in 1904 and sell all the output of what became known the "best car in the world". The year before he met Royce, Rolls had set a new land speed record of 93 mph. Two years after the meeting, the incomparable Silver Ghost was in production.

He came from a wealthy family but was famously careful with his money, even sleeping under his car to spend the night during long road races.

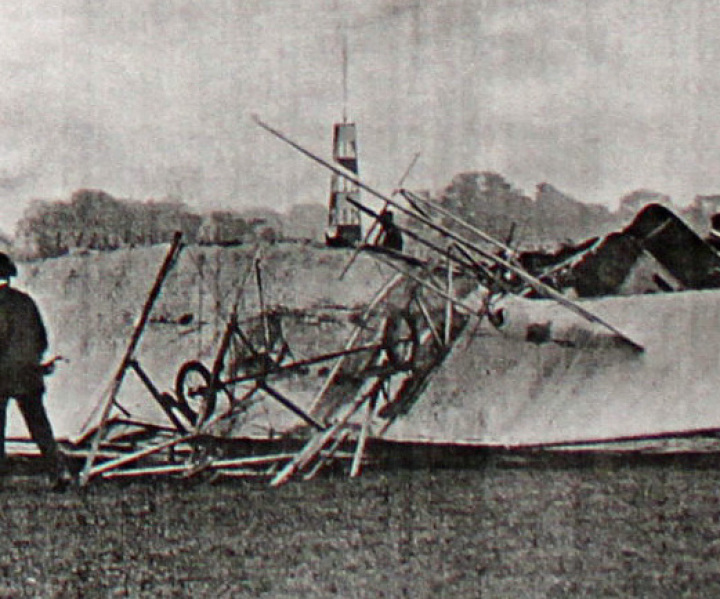

He was the first Briton to die in a powered aircraft accident when he crashed at Southbourne, in Bournemouth, on 12 July 1910 during the first international aviation meeting held in Great Britain. Royce, the ruthless and perfectionist engineer, was in tears when he heard of Rolls' fatal accident.

The event, hosting flying competitions as well as displays, was part of the Centenary Celebrations of Bournemouth.

One of the competitions was to land as close as possible to a touch-down point. Rolls had tried to improve on an earlier attempt, which had brought him a 3rd prize, but the recently modified tail of his aircraft, a Wright Flyer, failed and the aircraft plunged to earth from about 80 feet. The modification gave more control but broke up in the very gusty conditions. So died Charles Rolls at the age of 32.

In June 1910, Rolls had used his French-built Wright Flyer for a non-stop return trip across the English Channel. This improved on Bleriot's single crossing and further raised awareness that Britain was "no longer an island". Despite his protestations to the War Office about the lack of any effective aviation policy to help defence, the government could then see no future for military aviation. However, somewhat later, they were quick enough to approach Royce for aero engines for the Great War.

On 12 July 2010, as part of Bournemouth’s Bi-centenary, commemorative events included unveiling of the memorial plaque (refurbished by Rolls-Royce plc), and a Spitfire flying display for all, including local schoolchildren.

Each year, there is a commemoration at the memorial plaque which is out of public view in the playing fields of St Peter’s School. The next objective is to create a heritage feature to commemorate both Charles Rolls and Britain’s first International Aviation Meeting.

The link to the site of the registered charity, the Charles Rolls Heritage Trust, is:

Publications including Rolls

There are two books to mention here, both referred to under the BOOKS PUBLISHED tab: Charles Rolls and the First Bournemouth Air Show and BOURNEMOUTH THE AVIATION PIONEERS AND ROLLS OF ROLLS-ROYCE. The first was by me and published in 2019 by the Charles Rolls Heritage Trust (CRHT). The second was a team effort by the CRHT and published by the CRHT in November 2020. The first sold out within weeks and, writing this at the end of November 2020, the second has just gone on the market.

12 July 2010 Bournemouth

As the centenary of Rolls' death approached in 2010, a number of people, locally headed by the late Tony Harrington MBE, got together to arrange the first recent commemoration. It was quite a major event due to it being 100 years from the aviation meeting's fatal accident and 200 years from the founding of Bournemouth by Lewis Tregonwell as a watering place. Both St. Peter's School and St. Katherine's School were heavily involved. MP Tobias Ellwood gave a talk just before the Spitfire fly-past.

Here is the existing plaque located in the northern corner of St. Peter's School playing field, both installed by Rolls-Royce and since refurbished by the company for the centenary of Rolls' death:

Annual Commemorations

This is the event notice for one commemoration.

It can be seen where the existing plaque is located a short distance from the site of the fatal crash but on private land occupied by St. Peter's School.

Each year, the Rolls-Royce Enthusiasts' Club is invited to attend so providing a very tangible display of the Rolls' legacy. There are speeches by the Chairman of the Charles Rolls' Memorial Trust, the MP and the Mayor of Bournemouth, as well as a service conducted by the local vicar.

After this has taken place, there is normally

an aviation-based and relevant talk in a nearby hall.

Life and Times of Charles Rolls

Although it is only possible to give the briefest of descriptions under this heading, I hope that it is sufficient to explain why he is highly recognised and should be remembered despite his death at the age of only 32 years.

One legacy is that he co-founded Rolls-Royce Ltd following a meeting with Henry Royce on the 4th May 1904. The company has gained world-wide renown and importantly gave us the Merlin engine. This powered the famous Hurricane and Spitfire fighter aircraft that were used to protect and save Great Britain in the dark days from July to October 1940, now known as the Battle of Britain.

He helped and sponsored the Short Brothers through difficult times by buying balloons and aircraft from them as well as providing business advice. The brothers created the world’s first aircraft factory and went on to provide aircraft for the Royal Naval Air Service. Later, they built the famous Sunderland which provided significant service during the Battle of the Atlantic in safeguarding the supply lines from the USA at a critical time during World War II.

Rolls created a world record when he made a double crossing of the English Channel in June 1910, so finally making the point that Britain was no longer an island and vulnerable to attack from the air. Until then the Government deemed flying to be a rich man’s sport unworthy of official interest despite the fact that Germany and France were experimenting with aeroplanes for military uses.

Rolls co-founded the Royal Automobile Club and the Royal Aero Club. Both organisations became the main authorities of the day. He was also a Government advisor who explained that an air force was essential for the country’s defence. Although at the time it was decided that these new-fangled things were not of any military use, that view was swiftly changed by the First World War.

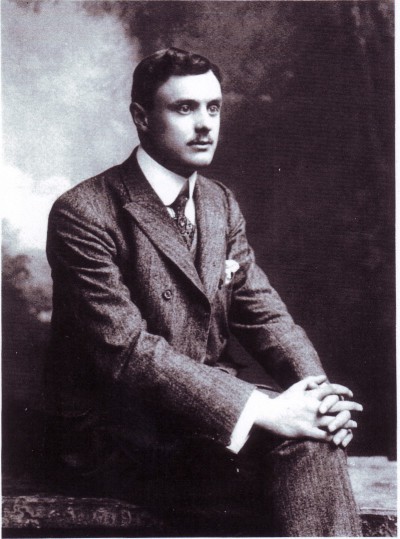

This is the family's favourite photograph of the eccentric, penny-pinching, sarcastic yet popular and charming Charlie Rolls.

And here are some brief miscellaneous notes in no particular order, used for giving a talks:

What must it have been like to fly a 1910 bi-plane: coat/muffler/cap; 60 mph/timber framework/open air; noisy engine/windy/no parachute?

Early take-offs involved attaching a heavy weight to the plane and dropping it from the top of a pylon. The plane could thereby be accelerated to launch speed by the time it reached the end of its launch rail.

On one occasion a horse dragged his plane to the take-off point and later dragged the wreckage back to the factory for repairs. When attempting his channel crossing record, his ground crew at Dover lived in a tent next to a hangar. Amazing times.

But maybe Rolls did not notice the deprivations – he was an aviation pioneer.

Rolls on flight: “a fresh gift from the Creator, greatest treasure yet given to man.” Just before his fatal flight he told a reporter: “All good engineering calls for casualties – so what? It was once my ambition to arrive at the Golden Gates on wheels, now wings…”

He knew about and cheerfully accepted the risks whilst being famous for safety checks.

What was he like? – Some miscellaneous facts: wealthy background; family housed 60,000 of the working class in 1906 London; coat of arms said Speed and Truth; Eton; Cambridge; captain of university cycling team; supposedly mean yet gave a cripple’s ward to a carpentry school; “one of the strangest of men and one of the most lovable”; adored Wagner.

He had two nicknames “Dirty Rolls” due to being oil-covered and “Petrolls”; national celebrity; patriot; worked for a time in railway workshops at Crewe; co-founded Aero Club of UK in 1901; reserved; in the Oxfordshire Light Infantry; owner of 6 planes; he entertained fellow balloonists by playing London airs on a penny whistle when aloft; he tested model gliders from a balcony at the Albert Hall; he was a flamboyant character who liked a glass of cider; Brabazon said he had “marvellous hands.”

He fitted well with Royce because they both had the same vision – to make the best car possible and many would say succeeded. The initial plan that Royce would make them and Rolls sell them worked well until Rolls got diverted by talk of the Wright Brothers at a New York motor exhibition.

He was more far-sighted than the government, which adopted his military aviation advice only belatedly and also the Rolls-Royce Board, which first declined his plan to make aero engines but did make them later.

He died just 6 years after meeting Henry Royce and 4 years after co-founding Rolls-Royce. By 1910, he was planning to start the Rolls Aeroplane Company to manufacture the Rolls Powered Glider. “Rolls died with great promise unfulfilled.”

There is no doubt that the man his friends knew as Charlie Rolls had increasingly been captured by the excitement of powered flight and this was to the detriment of his work for car maker Rolls-Royce. But Henry Royce wept openly at the loss of his friend to aviation.

The time taken for his record to be the first to cross the English Channel twice without stopping was 95.5 minutes. It was a great boost to the country that had fallen behind in the aviation stakes. For instance, not one of the 23 aircraft in the August 1909 French competition had been British.

On 12 July 1910, there were 20 to 25 mph winds; aviator Dickson had previously wrecked his plane on the same Bulls’ Eye competition which was soon to claim Rolls’ life; aviator Grahame-White begged the judges to cancel as the wind speed was unsafe but they refused; Rolls’ plane broke up and within minutes his body was surrounded by friends in tears.

Archive

The Charles Rolls Memorial Trust (Registered charity no. 1174592) has deposited for public reference and research purposes a comprehensive archive at the Heritage Zone of the Bournemouth Central Library.

Slides

Contact

Any questions or comments welcome via the "Contact" folder which has the Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) security feature, shown by a padlock at the start of the website address line and "https" instead of the "http".