Christchurch Curiosities

In this, my first book about Curiosities, there were real problems in finding out what had been happening.

How can one relate the story of a residual section of Saxon wall in a council car park when there is disagreement about its authenticity? Is there a genuine safety risk attached to the High Street due to large disused beer cellars running beneath the highway? The cellars have been sealed off and appear to have been left unseen for many years. Did the Priory Church, of which many records were destroyed by fire, once have a central tower and spire, long since removed? What was to be done about all the uncertainties?

Since I could find no perfect solution to the problem, yet the curiosities were too fascinating to be left out, they have been included but with due warning about the doubts. I hope they will be resolved in the future. As an example, I show below the plaque over the Draper's Chapel giving some circumstantial evidence for the central tower and spire:

As for the other book on Curiosities, please find below the chapter headings in order to show the sort of topics included:

- Christchurch Nelson – a fund-raising dog

- Saxon wall controversy

- Bow House and a nightclub under the High Street?

- Pig-killing and life between the Wars

- Flambard – the hated founder of Christ’s Church

- Remarkable Mudeford family

- High price of leather and hobble-de-hoys!

- Henry VIII’s last-minute reprieve

- Unique river that “freezes the wrong way round”

- Pipe, boot and river keeper

- Why is the town called “Christchurch” today?

- Invasion scare of 1539

- Some ancient decisions of Christchurch Corporation

- D-Day from Hengistbury Head

- Can the Priory Church endure?

- Humour and hardship at the Petty Sessions

- Second miraculous beam

- Eels of Christchurch

- Mudeford in 1900 with Florence Hamilton

- Normans, weather vanes and salmon

- Astonishing catches and the Royalty Fishery

- From helping the poor in 1372 to helping the traffic now

- Stocks and ducking stool – for visitors

- King Canute, climate change and Christchurch

- Now we have trams!

- England’s last surviving bus turntable

- Oliver Cromwell and the salmon thieves

- Wartime evacuation to the Cadburys

- Childhood memories of a Victorian mayor

- Town that should not be here

- Railway workers’ rescue boat on River Avon

- Did the Priory’s old tower and steeple collapse?

- Billy Combe’s last fight

Although the town today is highly attractive to both residents and tourists, it was not always like this being mainly a poor fishing village. When persuading Henry VIII to spare the Church, the Prior's description of Christchurch was very downbeat:

"That where the said place is situate and set of a desolate place in this your Realme and in a very bar[r]en Countrey out and farr from all high wayes in an angle or a corner."

Even by the 1930s, from this account of children's entertainment, life then was, as elsewhere for that matter, a far cry from today:

"When a crab is dead, it’s not fit to boil so they used to be buried in the garden and, for entertainment, we used to put a piece of black cut line, that’s fishing line, on the legs of these big crabs and walk across the road to the Catholic Church and put them by the wall and bring the string across the road under the gate and one of us used to sit on the wall at the top and when the old ladies used to come by, the one at the bottom used to jerk these crabs across the road and ‘course, the old girls used to scream and jump and tear off down the road. This is our only entertainment…."

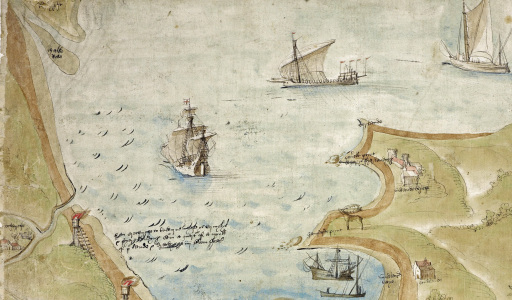

Two more illustrations from the book are given below. The first, from Chapter 12, is a 1539 map extract giving a pictorial assessment of invasion risks and defences. Christchurch is at the bottom left of the image. The second, from Chapter Nine, shows something of an ice battle on the Avon after it had frozen, for reasons explained, the "wrong way round," i.e. from the bottom upwards.

BOOK EXTRACT

Again, it was with some difficulty that I found what might be termed a typical chapter to include here. In the end, I chose a brief one that demonstrates humour and conflict were just as alive and well in nineteenth century Christchurch as they are today:

High Price of Leather and Hobble-de-Hoys!

Nineteenth century Christchurch produced a number of anonymous and perhaps eccentric-sounding letter writers to the Christchurch Times. In this first typical example of the genre, we have a genuine concern about the tax-induced price of leather expressed with wit, charm and imagination. Mention of Paterfamilias implies the writer is the male head of a household who has concluded that the foot is both under-rated and badly treated! He also sounds well-read to know all about the essay published in 1833 by Sir Charles Bell, a most eminent doctor, extolling the merits of the human hand in a document running to more than 200 pages.

There is a probable double-meaning at the end of the letter. A corn cutter was the name of a Victorian occupation we would now call a chiropodist whilst a corncutter is also a special blade for cutting corn stalks. Why should the government get extra taxes from leather goods without any prior contribution (sowing) and/or why should foot doctors benefit from the inherent defects of leather boots when a soft substitute might be better? Readers may interpret the letter differently.

SIR, – You remarked last week upon the high price of leather. The frightful price which it is assuming under the dynasty of a sixteen penny income tax sets Paterfamilias on the look-out for a substitute. The wonder is John Bull never thought of that before. What a bundle of habits we are, what slaves of the tyrant fashion. Why an eminent man (Sir Charles Bell I think) wrote a book, a big one too – a Bridgwater Treatise – to teach us the use of our hands; can it be, then, that nature designed the foot as in reality a part of what anatomists term, I believe, conventionally, the inferior extremity. To shoe the cat with walnut-shells was, in our schooldays, “fun;” yet what a philosophic lesson if read aright. Look at the ballet dancer – the tight-rope dancer – the sailor – the professional pedestrian who walks for wagers – how little they encumber the foot. Nor are instances wanting of the foot being educated to supply the place of hands, in the use of knife, scissors, and other instruments. Man may be superior to monkey in head, certainly not in heel. Oh, but thin shoes have always been held fruitful of colds, coughs, consumptions – query are the shoes or stockings most at fault? who now-a-days confesses to aught so plebeian, as “stout knitted hose,” such as our grandmothers delighted to work. The stoutest boot (of leather) soon ceases to be waterproof, and once soaked retains moisture in proportion to its thickness, to be given out again insidiously. Why not wear something of the slipper kind, of some worked materials; surely some soft substitute for leather could be found. Why wear the high wellington boot? What is the use of such; is it for protection? If so, why in the name of wonder wear it inside the trowser. The days of the hat are numbered, then let us kick the old boots after for luck. Head and feet both cry aloud for reform. Why should the corn-cutters reap what they did’nt sow?

Yours obediently,

SPRING-HEELED JACK

Christchurch, January 28, 1857.

Turning to the second writer, still in the late 1850s, it may be a mistake to consider anti-social behaviour to be a modern malaise with a variety of modern causes. As this letter shows, the young men of the town were not universally of “morally upright character” as the Victorians might have said.

SIR, – I have been so constantly and seriously annoyed Sir lately that I cannot refrain from writing you upon the cause of my annoyance. I saw in your paper not long ago that a poor old woman, on passing near the corner at Purewell, was stoned by a lot of worthless hobble-de-hoys, who towards evening congregate there and pass their idle time in using filthy language, and in making remarks on, and otherwise annoying, the passers by. I am constantly compelled to pass along the streets in the evening, and the abuse I have received, the disgusting language I have heard, and the disgraceful conduct generally of the young men at various corners in the town, often causing an actual obstruction to the passenger, have convinced me that the morals of the labouring poor are low here, and that something is required to make them know better.

Yours, &c.,

A MARRIED WOMAN

Christchurch, May 18, 1858

Slides

Contact

Any questions or comments welcome via the "Contact" folder which has the Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) security feature, shown by a padlock at the start of the website address line and "https" instead of the "http".

To purchase the book, it may be simplest to do so from Bookends, Christchurch or via Amazon. If you would like a signed copy, let me know and an arrangement can be made.