Air Raid. A Diary and Stories from the Essex Blitz.

One day, I was looking through some old family papers and rediscovered my mother's diary running from the start of the Blitz until my parents' house was bombed. It was a dramatic account of how ordinary British lives were turned upside down by Hitler. Having decided that they would not have minded publication, I began to find out about the background. Lord Tebbit has Essex connections and kindly agreed to write the Foreword. In addition to the diary as annotated by researched information, the book describes the circumstances of both family and war. The history of the suburb of Upminster, the impact upon it of the Blitz and the family's house move to Bournemouth are all covered.

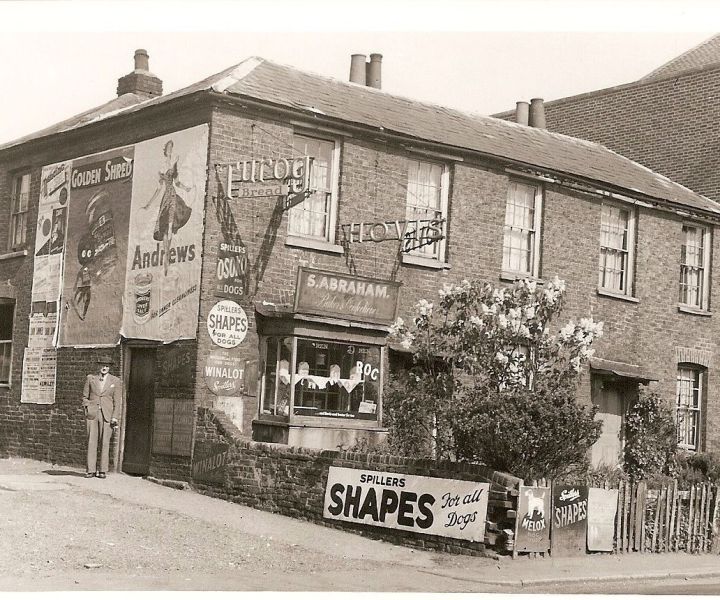

A particular reason, for the amount of bombing around Upminster where they lived, was the closeness of the Spitfire airfield at Hornchurch. When you reflect on the calm of the pre-war era, it is almost impossible to visualise the sudden warning sirens, loss of life, serious injuries and disruption caused by the bombs. The pictures which follow give an idea of the calm before the storm:

The contrast with the effects of war on such a place could hardly be greater:

Sometimes, information would be passed on by local people to one another and be less than accurate. But that is only to be expected. However, my impression is that few of the diary entries are other than simple reporting of what happened.The following extract is from the diary itself together with some notes on one particular raid:

Raid 22. Aug.31st 6pm. (13 bombs)

H. still at work. Very bad raid. Blast in shelter threw earth on our legs – made Mrs. T’s nose bleed (2 days). Houses at corner of Wingletye Lane smashed – also Hacton Lane where 12” gas main hit. H. saw Jerry bale out over Upminster way. Spitfire down at Ockendon. H. travelled home through raid & had continual fighting over train. Cooked chicken in honour of wedding anniversary. Just done at 6pm. Left it in oven. Dished up when H. arrived (6.20pm) and ate dinner in shelter. Mr. H. acted as lookout while I got it ready.

St. Chad’s playing fields hit.

RAID 22 (Note on this raid)

Thirty bombers returned and destroyed two parked Spitfires and killed a member of the ground crew. An RAF pilot, who had baled out and finished suspended from a high wall, was nearly attacked by an angry mob that believed him to be German. A house was demolished at Hacton Lane.

BOOK EXTRACT

Apart from publishing the diary of how the Blitz affected an ordinary family, I felt it would help to give the context which would have been in the minds of people at the time. Here is one example of the Phoney War stage.

Phoney War and Civil Defence Preparations

Long after the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 and the Declaration of War on Germany by Chamberlain two days later, and despite the most appalling forecasts of air raid damage, little seemed to be happening. The general impression of inactivity duly became known as the Phoney War, or Bore War. The air raid sirens, which had sounded within a few minutes of the Prime Minister’s 11 a.m. speech on 3 September, were soon found to have been operated in error. The culprit was a French plane over Kent without a flight plan, but on a very tense day with most expecting the air raids to begin without delay.

However, much essential defence work was already in hand and now continued. The newspaper reports in Figs. 19 and 20 give a feel for the times. While Hitler was diverted with Poland, the U.K. became stronger. It had not been long after Chamberlain’s apparent success with Hitler at Munich in 1938, before the euphoria about “peace in our time” evaporated, the expectation of war set in, the gas masks were issued and barrage balloons appeared around London. A massive civilian readjustment was in progress as a direct result of the official expectation of German bombers.

Many firms, trades unions and civil servants left the capital at short notice, causing a large oversupply of property on the market. Hospital wards were largely cleared to the provinces to allow for a big intake of air raid casualties. Although the people were not told at the time, the official view in government was that widespread panic was to be anticipated. How wrong that proved. The more extreme pre-war predictions had been dire indeed: a general flight from towns, people crushed to death in the panic, widespread starvation, epidemics of disease and so forth. It was also forecast that the nation more stoic under bombing would be the victor.

There was an element of ambivalence in public opinion: although the storm ahead was keenly seen, the early lack of raids created frustration and boredom among the newly-formed emergency services and public discontent with their cost. One fire fighter felt ashamed that the monotony was getting him down and “half hoped for something to happen.” There was particular dislike for the ARP wardens, who were perceived as officious. Many new Civil Defence workers were surprised and perhaps disappointed at the quiet start to the war and resigned their posts to join the services. With the boredom, complacency set in and one report from October 1939 even said that most felt there would be no air raids.

Slides

Contact

Any questions or comments welcome via the "Contact" folder which has the Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) security feature, shown by a padlock at the start of the website address line and "https" instead of the "http".

To purchase the book, it may be simplest to do so from Amazon. If you would like a signed copy, let me know and an arrangement can be made.